By Joshua Kindl, Georgina Goddard, Zac Gay & Lachlan Moffet Gray

In January last year, Penrith hit 47.3 degrees Celsius and was – for a matter of hours – the hottest place on the planet.

Average temperatures are increasing across the country, but Western-Central Sydney is defying normal trends and getting hotter, faster.

Samantha Webb, a Chatswood resident who has worked in Parramatta for the past three years, says that the temperature change from Sydney’s west to other parts of the city is not only noticeable, but substantial.

“I really do notice there’s a big difference out here to Chatswood. I can watch the thermometer on the car drop or increase as I’m driving either way.”

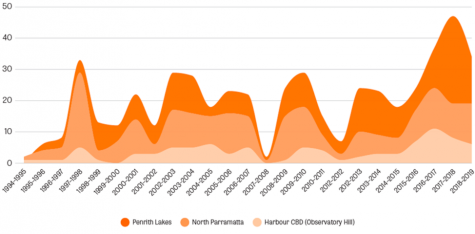

Last summer, Sydney’s eastern suburbs experienced six days above 35 degrees Celsius. The central suburbs around Parramatta experienced 19 days and the west, 37 days. This was the highest number in the Greater Sydney area.

Number of days above 35 degrees Celsius, July 94-June 19 (Greater Sydney Commission, Bureau of Meteorology.

A submission to the NSW parliament by Greening Australia also revealed that January mean maximum temperatures in the West have increased at a pace of 0.65 degrees per decade, over twice as much as eastern Sydney’s 0.28 degrees per decade.

Why is Western Sydney getting hotter, faster?

Dr Gloria Pignatta, a lecturer in the Faculty of Built Environment at UNSW, says Western Sydney is already predisposed to higher temperatures due to its geographical placing.

“Even if you’re able to cool down one specific area or new development … then you will have hot air coming from other areas that are not mitigated that will modify your effort. It’s really tricky to find a solution to reduce the temperature locally, especially with the predictions of the increasing temperatures in a few years due to climate change.”

The Western Sydney Regional Organisation of Councils (WSROC) estimates that urban heatwaves increases mortality by 13 per cent. In the Nepean-Western Sydney region, this increase would equate to approximately 860 additional deaths per year, extrapolated from NSW Government statistics.

These heatwaves form as a result of the Urban Heat Island effect, explained by Dr Pignatta as “a phenomenon where the temperature in a city is much higher than the temperature in a rural area at the same time.”

Count the cranes; Count the trees (Photo: Joshua Kindl)

According to a recent OECD report, the Urban Heat Island effect warms urban areas 3.5-4.5°C more than rural areas. Furthermore, climate change forecasts by the NSW government project that average air temperatures could increase by up to two degrees Celsius in the next fifty years.

Dr Pignatta adds that Sydney has a positive urban heat island, meaning that temperatures in our densest urban areas, such as the so-called ‘Second CBD’ of Parramatta, are significantly higher than in the cities suburban or fringe areas.

As a result of rising temperatures stemming from the Urban Heat Island effect, cities will become less liveable, industries will suffer, and the urban identities of these urban areas will change altogether. Public amenities, such as public parks and playgrounds, non-air conditioned forms of public transport, and even beaches and pools will become unusable in the extreme heat, severely impacting quality of life.

The economic costs of such an impact are enormous: $6.9 billion is lost annually in Australia due to reduced productivity resulting from forms of occupational heat stress, such as heat stroke and heat exhaustion.

These negative consequences could arise with increased population growth necessitating more development. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, no Sydney region has grown faster since the turn of the 21st century than Parramatta, with over 145,000 added to the area in the past 18 years.

Local councils claim they have a plan to combat the rising heat in the form of ‘cool planning’.

Cool planning involves tailoring urban planning to facilitate the escape of heat. Parramatta Council is leading the way, collaborating with UNSW’s Centre for Low Carbon Living to redesign Parramatta’s Phillip Street, allowing heat to escape the precinct. Initiatives include misting units, wider footpaths, more trees and pavements that naturally absorb less heat.

Dr Pignatta labels these efforts as a means to create “thermal comfort”, decreasing levels of thermal stress on citizens.

Parramatta City Councillor Phil Bradley notes that measures such as these have been raised by citizens who live and work in the area, saying ‘the public is constantly bringing concerned about the number of trees being removed.”

Ms Webb concurs, saying current public spaces and amenities are not functional given the extreme temperatures in the area.

“It doesn’t really matter what they do. I work close to the park, but I don’t go over there because it’s just too hot and I just find there’s very few facilities over there; like if you wanted to go for lunch or anything it’s just not so convenient

“It is roasting out here in the summer.”

The Centre for Low Carbon Living claims that expanding these efforts across Parramatta could lower local temperatures by as much as two degrees Celsius – the level at which the state government expects temperatures to increase across Sydney due to climate change.

Accordingly, cool planning is coming under criticism as a band-aid solution meant to distract from the high levels of development supported by all three levels of government, and inadequate climate action.

Referencing this criticism, Cr Bradley says that recent efforts to increase the level of natural flora in the area has so far been unproductive.

“When there has been planting been made to replace some trees they are not properly removed and die, or are destroyed by vandals,” he said.

Dr Pignatta says that effective cool planning solutions will not be able to be implemented until companies and governments are able to efficiently balance cost against the needs of the local population.

“The difference between traditional materials and [cool planning] solutions are really high. It’s okay in Europe or America, but here it’s something that’s not sustainable for companies or local governments

“I think the policy needs to make [cool planning solutions] mandatory in order to reduce the cost and make the current technologies be put into use. But nobody will do that, because it’s not convenient,” she said.

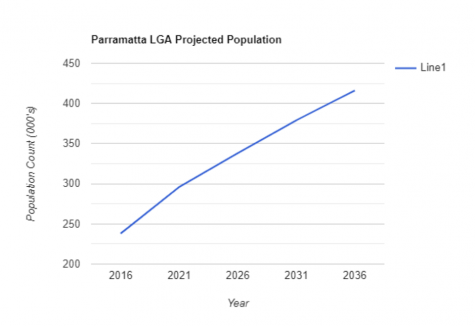

Parramatta’s Projected Population by Year, 2016-2036 (NSW Department of Planning).

Cr Phil Bradley is supportive of cool planning initiatives, but believes it is “debatable” whether or not the full impact of increasing heat can be alienated.

“Parramatta’s population could grow up over 400,000 people by 2036, almost doubling the population we have now.

“In my view, if the population is to double, we need double the amount of green space, pools and community services on top of cool planning efforts…The council is struggling to provide the proportional increase in services – there is going to be more than $100 million of shortfall,” he said.

Cr Bradley further states that Parramatta Council is doing its bit to fight climate change – joining the peak body for councils in NSW in declaring a climate emergency and by adding over 100,000 KW of solar power energy to the area through incentive schemes – but thinks that unless population growth eases in the near future, urban areas like Parramatta will continue to get hotter and hotter.

“Population growth is a problematic issue. There has been a view expressed by some, including the planning minister, that we should spread population growth more fairly and evenly around the system instead of targeting a few growth areas,” he said.

Dr Pignatta also warns of the dangers presented by an increase in population.

“We need to be careful because we are asking people to go in these areas where it is very hot, we are building new developments and we are transforming the area. This will not help and people will suffer,” she said.Ms Webb hopes that action will soon be taken in support of Parramatta.

“I love this space and I like coming down here… it’d be nice to see if they put something in place here to soften it all a bit.”

— Joshua Kindl, Georgina Goddard, Zac Gay & Lachlan Moffet Gray