Buying drugs has never been so streamlined. On a number of open-access websites, digital “menus” offering everything from hydroponic cannabis to psilocybin mushrooms are just an encrypted message away – complete with prices, emojis, daily discounts for bulk orders and free delivery.

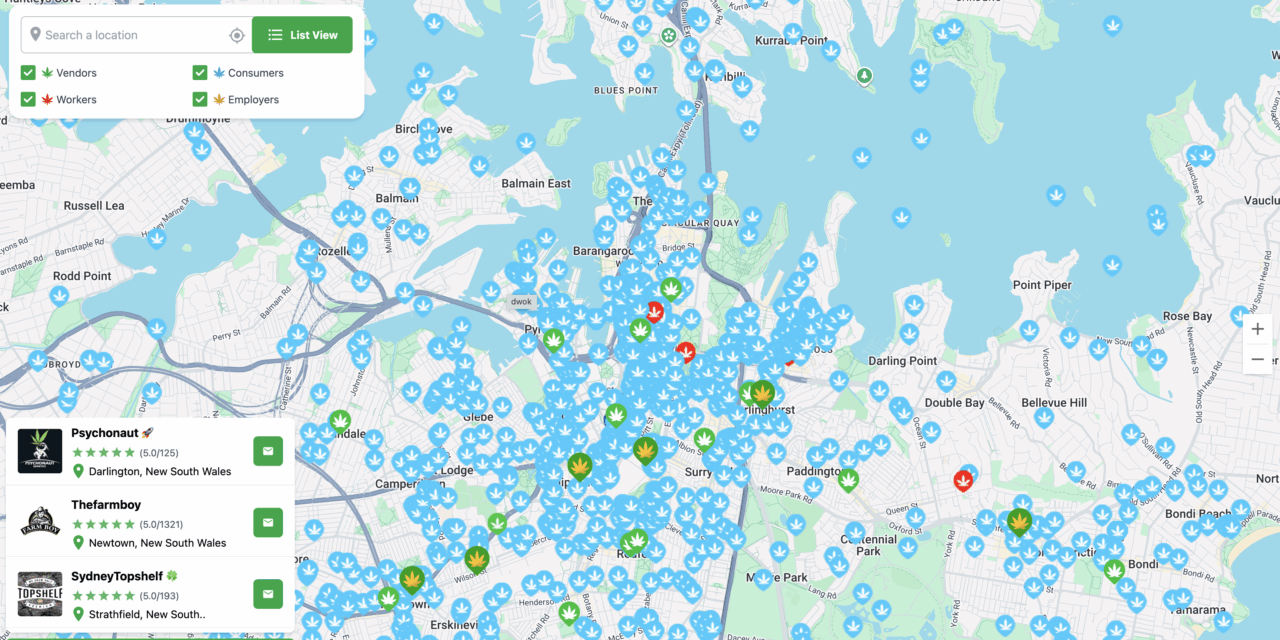

For those who know where to look, buying marijuana can be as simple as ordering a pizza, with convenient realtime maps of drug dealers in almost every suburb of Sydney to choose from. A quick exchange with a vendor and 30 minutes later a rider resembling any typical food delivery service shows up at an arranged point to complete the deal – in cash.

Among these underground digital networks sits LeafedOut, a US-based cannabis-specific platform that bills itself as a community for connecting patients to medical cannabis.

But, an investigation by Central News has revealed the site has been hijacked in Australia, using its geolocation technology to cultivate an online black market for cannabis.

How it works

Unlike the dark web, LeafedOut operates on the surface web: the publicly accessible part of the internet anyone can find through a simple Google search. Users can search by postcode or city to reveal an interactive map of their area. In Sydney, hundreds of green pins mark ‘vendors’, while blue pins herald ‘consumers’.

Each vendor post acts like a digital shopfront, listing strains, quantities and prices. Buyers are encouraged to move conversations onto encrypted apps such as Telegram or Signal, where sales can be arranged discreetly away from the reach of moderators or law enforcement.

This handoff allows sellers to use LeafedOut as a discovery tool while relying on messaging app’s privacy features to negotiate deals and share delivery details beyond the reach of platform moderators and authorities.

Semrush web analytics show interest in LeafedOut is rapidly growing. Over the past month, the site attracted more than 243,000 visits worldwide, a 50 per cent increase on the previous month.

Cannabis remains one of the most widely used and accessible illicit drugs in Australia. According to the 2024 Ecstasy and Related Drugs Reporting System (EDRS), 94 per cent of Sydney-based participants reported cannabis was either “easy” (31 per cent) or “very easy” (63 per cent) to access, a figure that’s been steadily increasing over the past five years.

Dr Andrew Childs, a criminologist at Griffith University who studies online drug markets, says the rise in accessibility is due to the digitisation of black markets.

“Even if you go back to some of the really early days of the internet, people were using really bespoke forums to exchange information on how to manufacture certain chemicals,” he said.

“Like markets for anything, whether it’s drugs or illegal products, they go to where the people are and they go to where the opportunities are.”

In a 2021 study, Dr Childs examined LeafedOut as part of a new wave of “surface web” drug markets – platforms that are openly accessible without the anonymous protection of the dark web.

He found LeafedOut occupies a unique space in the digital black market.

Drug dealers in these messaging platforms, they’re almost like content creators now.

“It’s really interesting because LeafedOut [is] very accessible to people, but it’s not attached to a social media platform,” Dr Childs said.

“The concern about using things like Snapchat or Instagram, or whatever, for dealing was that it’s linked to their name.”

By contrast, LeafedOut allows dealers to operate under pseudonyms, sidestepping the personal identifiers and public visibility that make mainstream social media riskier for illicit transactions.

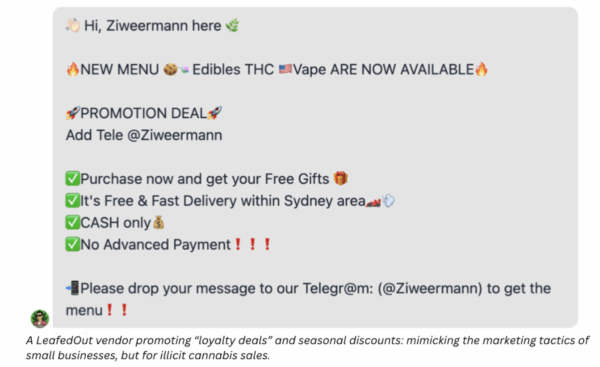

One of the most striking trends Dr Childs observed was how these online dealers are adopting the same marketing tactics as Instagram influencers or small business owners.

“One of the links we made as well was like many drug dealers in these messaging platforms, they’re almost like content creators now,” he said.

Screenshot of ‘Thefarmboy’s’ digital drug menu on LeafedOut, showcasing cannabis strains available to purchase.

Vendors post updates in the same way lifestyle influencers share new content, complete with seasonal sales, competitions, and product drops.

“Promo deals, 24/7 communications, they take influencer tactics and how people run their social media pages into these illicit sorts of spaces,” Dr Childs said.

These operators rarely resemble the stereotypical image of a street dealer. Instead, they present themselves as approachable, professional, and responsive — offering fast replies, friendly emojis, and loyalty discounts.

‘Thefarmboy’ is one of Sydney’s highest profile and most organised vendors operating on both LeafedOut and Telegram. It boasts over 1,300 five-star reviews on LeafedOut, underscoring a large and loyal customer base.

‘Thefarmboy’ is one of Sydney’s most active vendors, boasting more than 1,300 five-star reviews and using the platform’s visibility to build a loyal customer base. Image: Screenshot from LeafedOut.

In fact, so popular is Thefarmboy, it is at times named among the platform’s ‘Vendors of the Week’. Its online profile boasts “best quality without pgrs, cheapest price, CASH face to face, absolutely no bullshit!”

Other top vendors on LeafedOut include ‘SydneyTopShelf’ from Strathfield and ‘Psychonaut’ based in Darlington, illustrating a growing and competitive market.

A LeafedOut vendor promoting “loyalty deals” and seasonal discounts, mimicking the marketing tactics of small businesses, but for illegal cannabis sales. Image: Screenshot from LeafedOut.

NSW Police is aware of LeafedOut and say online drug sales aren’t new — but they remain a major challenge to police.

In a statement to Central News, the NSW Police said they are targeting the supply and manufacturer of illicit drugs, but they warn that real change requires reducing demand, stressing that while ever “someone is willing to buy [drugs], there will be criminals willing to supply [them] for profit”.

But while police continue to target online suppliers, some experts argue the problem lies less with technology and more with policy.

Policing vs Policy

Dr Alex Wodak, a veteran drug law reform advocate, Emeritus Consultant at St Vincent’s Hospital and president of the Australian Drug Law Reform Foundation, said prohibition has fuelled the very markets police are now struggling to contain.

“Demand for recreational cannabis has been strong in Australia for at least 60 years,” he said. “And as there is no legal source in Australia at the moment for recreational cannabis, other sources have emerged.”

Dr Wodak has long argued prohibition is unsustainable. He recalls being “dismissed and laughed at” when he first made his case publicly in 1987.

“Prohibitions generally fail. They often take a while to fail, but they generally do fail,” he added.

Dr Wodak says criminalising cannabis has created fertile ground for organised crime and street-level dealers to profit.

“[Prohibition] is in effect supporting organised crime, including the outlaw motorcycle gangs and all the other people who are basically criminals,” he said.

According to the Penington Institute’s Cannabis in Australia 2024 Report, the 12 months to June 2024 saw 14,733 cannabis-related offences, accounting for 36.9 per cent of all drug offences in the state.

While this represents an 11 per cent decline in the total number of cannabis offences from the previous year, the proportion of all drug offences involving cannabis has remained largely stable.

Smoking paraphernalia for sale at a Sydney tobacconist. While cannabis use is illegal in most of Australia, accessories like these can still be sold for “tobacco use only”. Photo: Zac Nikolovski.

“It’s insane that we are still arresting 70,000 or 80,000 young people a year, harming them for a lifetime,” Dr Wodak said. “And the people we inevitably catch are overwhelmingly consumers rather than suppliers.”

Public sentiment mirrors his argument.

The National Drug Household Survey tracks public support for regulation and decriminalisation every three years. According to the most recent report in 2022, support for decriminalisation of possession has grown to 80 per cent.

For him, the solution is not tougher policing, but regulation. “Prohibition ends up being an expensive way of getting bad outcomes – bad outcomes for health, social welfare, and also the economy,” he said.

“The more we regulate instead of prohibit, the better off we’ll be.”

Main image screenshot from LeafedOut.