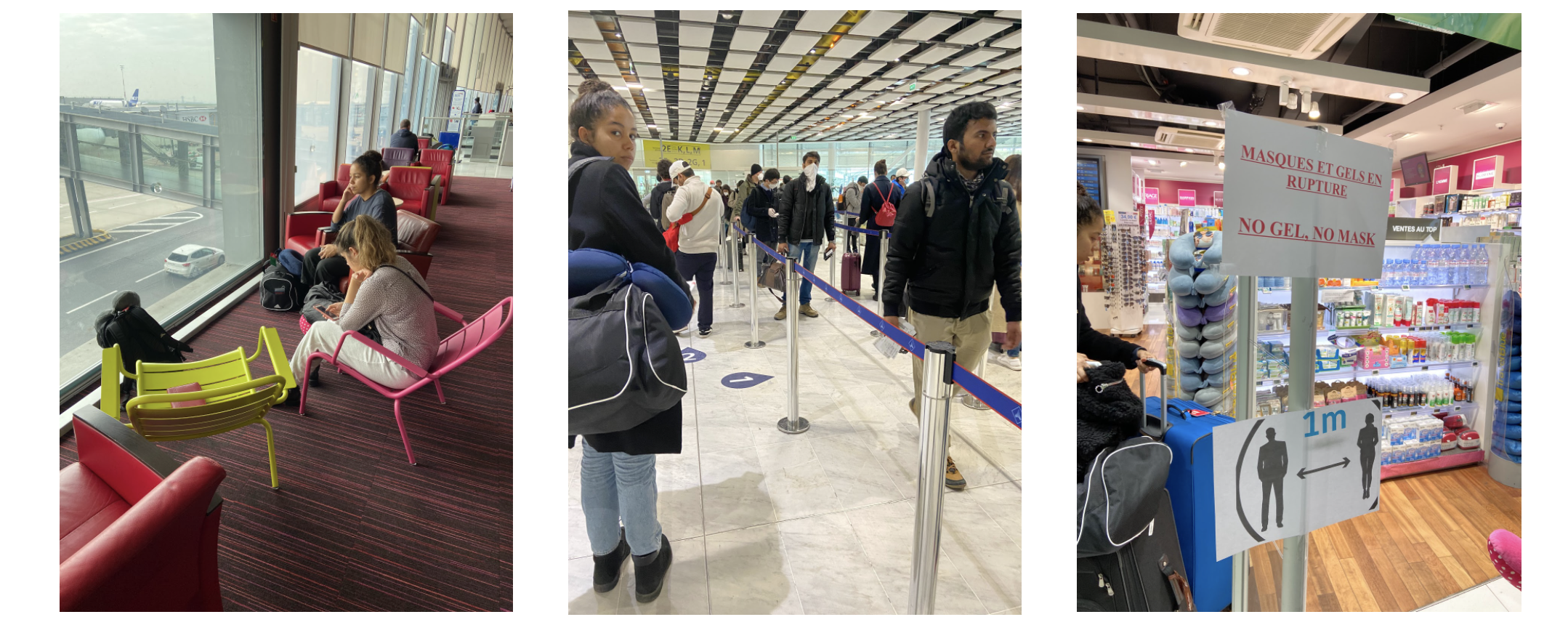

*(Photo: Laura Grassby)

Laura Grassby was one of the many exchange students forced to abandon overseas study when the coronavirus took control. She describes how home and host countries now seem worlds apart.

If you were to drive through my hometown, you would hardly know there was a pandemic tearing across the world.

Sure, the few shops on our main street are closed. But there are families on bikes, dog walkers, retirees, joggers. You can still hear the cows across the road at night, the frogs are still loud after rain and the garden looks the same.

But I feel different.

Not that long ago, in the space of a week, my life was turned upside down – just like the lives of so many others. I was forced to return to Australia ten months earlier than planned.

CAEN, NORTHERN FRANCE

Last year, I chose the small town of Caen in Northern France, to be the home base of my year abroad. I was there to learn French, to travel and to eat as many croissants as possible.

No-one was wrong about the weather, but what I wasn’t told, was how ridiculously lovely French people are; how soil doesn’t exist in Normandy, only mud; and that I could feel at home in a completely unfamiliar place within the space of a week.

At the beginning of March, COVID-19 was still a distant threat. I had been to Brussels, Berlin and Rennes, and my French was improving. My homesickness had been replaced by a sense that I was exactly where I was supposed to be.

Wednesday the 11th, was the first day I remember things feeling ‘off’.

I was trying to do homework but I couldn’t concentrate. I was thinking about the coronavirus posters now stuck to every door on the campus. That night, we had a farewell dinner for a friend, but we couldn’t seem to stop talking about the looming uncertainty. We talked and talked and talked, until no-one had anything left to say.

Around 3am Paris time on Thursday the 12th, US President Donald Trump announced border closures.

The effect was immediate. The following morning, 80 per cent of the American students in our building had left, as if they had vanished into thin air. The European students were also abandoning ship.

At 8pm the same day, French President Emmanuel Macron announced that all schools and universities were to be closed – immediately. More bad news. I was in one of the kitchens, listening anxiously to the live broadcast. English translations wouldn’t be live for at least another six hours, so I had to try my best to translate.

By that point, our group of five Australians felt depressed. We had planned a farewell for those leaving, but the cheap vodka and orange juice sat on the table, untouched.

On Saturday the 14th, President Macron raised the alert to Level 3.

All non-essential businesses would be closed, indefinitely, from the next day. Only supermarkets, doctor’s surgeries and pharmacies could trade. We were now in a foreign country that had declared a state of emergency.

At breakfast on Monday the 16th, the Australians left in Caen told me they would be going home. I was trying to stay in Europe for as long as I could.

No one knew how long these measures would last, and if I left, I would be saying goodbye to my dream year.

Within an hour I had a new plan. I would get on the next plane to Switzerland and stay with my extended family until it blew over. Ticket bought, I started packing my room. No time to waste.

At 3pm, Switzerland’s borders were closed.

It’s hard enough when everything goes sideways in your own country but when you’re in an unfamiliar place, in an unprecedented situation, how do you stop yourself from transitioning into an ‘everyone for themselves’ mentality? How do you remember to smile, to say thank you, to remain courteous – when your reality has been turned upside down in three days?

It was at this point that I found myself unable to sleep, eat or recall words in both French and English. Tempers flared and suddenly differences of opinion became a real sticking point.

Later that night, after a terrible and expensive pizza delivery, I made the decision that I would have to return home as well.

Many factors contributed to my decision. There was a real feeling governments around the world, including Australia, would follow the US and shut their borders. Airlines were already dropping like flies and there were stories of people being stuck in South America.

In the end, I wanted to make a choice while I still had one.

RACING THE CLOCK

10:00pm: Started to arrange the nearest flight home. Booked a private shuttle to Paris CDG airport. Booked a hotel.

11:00pm: Etihad grounded all its flights in and out of France. Managed to organise another airline.

12:00am: Paid for flight.

1:00am: Packed up my room.

4:00am: Received my flight ticket after 3 hours on the phone with the travel agency.

6:00am: Slept.

7:00am: Woke up, dressed and dumped all the belongings I couldn’t save on the free table in the lobby. The building looked like a war zone. Someone had set up a bed on the lounges in the lobby. Abandoned food and other items were piled up and spilling onto the floor.

8:00am: Dragged my bags out to the road. Reception was already closed. Dumped my key in the post box.

I was in a group that reached the hotel in Paris with 120 minutes to spare before the nationwide lockdown started. I started to relax a little.

But that afternoon, Singapore Airport announced it would deny entry or transit to all foreigners. This was a real problem for one of us, who was booked on a Singapore Airways flight.

If the UAE transit hubs did the same, our Emirates flight would be cancelled.

I immediately called our international helplines, to see if they had any current information. They all gave me the same response: ‘unfortunately, we have no more information than you do. Sit tight’.

When dinner time rolled around, we came across another problem. How would we feed ourselves if we couldn’t go outside to the supermarket or order food?

Panic started to set in. I remember walking around the deserted complex, going from hotel to hotel and asking to buy food.

It was like watching an apocalypse movie, except there was no off button.

The next day, we dressed for battle.

Three travellers; no masks; a quarter of a bottle of hand sanitiser between us – we didn’t know if we were going to make it to breakfast, let alone to Dubai.

This was the day, Wednesday the 18th, that DFAT placed a Level 4 travel ban on the entire world. This meant that most insurance policies would not cover us and the Australian Government might be unable to help if we were in trouble. Suddenly there was a real chance we could get sick – and even die.

Charles de Gaulle airport was a ghost town. Waiting for the others, I overheard another Australian pleading with the Emirates staff to let her board the plane. She had booked through a third-party and her name was not in the system.

The next 24 hours were a blur.

We saw DIY hazmat suits; passengers fighting over free seats; empty A380’s and plenty of airport lounges. Vending machines became our best friends and my hands became so dry from the sanitiser that they started to crack and bleed.

As we boarded our connecting flight in Dubai, a man behind me turned to his partner and said: “I’m never leaving Australia again”.

HOME

On Thursday the 19th of March, we landed in Sydney.

I was sad, but relieved. I texted my parents, saying that I might be delayed with medical checks in the airport. To my surprise and dismay, there were no such checks. Not one.

Frozen at the exit point, I watched as hundreds of my fellow passengers streamed out into the night. Many had flu symptoms. I’d heard their coughs and the sniffles on the plane, same as everyone else. We were required to state whether we had been to China, Iran or Italy. If you answered no, you were free to leave and start your 14 days in self-isolation.

France was one of the fastest growing hotspots for COVID-19 at that time, according to Worldometers.info. On the 20th of March, France had recorded 12,612 cases. Ten days later, 44, 550 cases. It remains the sixth most affected country in the world.

When I finally saw my parents waiting for me in the carpark, I realised that I wasn’t protecting myself from others anymore – I had to protect them from me.

I was a possible contaminant. A threat.

It wasn’t until I was 3-4 weeks out of my quarantine period that the Australian Government opened-up testing to overseas travellers and widened the symptom criteria. Despite my best efforts, I could not access a test, even with confirmed cases on my second flight.

Life is now an odd combination of checking emails, cups of tea, at-home workouts and TV-shows.

It’s hard to not immediately find myself in arguments. Arguments with friends, family, the government. Seeing a different side, a more threatening side to the pandemic that most Australians haven’t experienced, is tough.

I feel like an alien in my own country, freshly arrived from a parallel universe.

While the last month has been far from ideal, I’m not a nurse or a doctor. I’m unemployed, but I’m not trying to juggle working from home and looking after children. I’m not trapped in an overseas country and wanting to return home. I don’t have the virus.

I am one of the lucky ones.

— Laura Grassby