Chiang Mai | At first, James* didn’t realise he was wanted for arrest by Myanmar’s junta.

He had gone into a bank to deposit money for the company he worked for, but instead was told the bank was closed.

It was a set up.

“[I was told], ‘today we are closed, but we will do it special for you’, and I didn’t realise, so I went to the bank, and there was only two staff of the bank, and there was military intelligence,” James tell’s Central News.

Despite not being a journalist, James’ place of employment at Mizzima, a Burmese independent news organisation, meant he was put on a wanted list for arrest.

He didn’t know it at the time, but that April day would mark the beginning of a seven-month ordeal in some of Myanmar’s most brutal prisons and camps, where he was beaten and threatened with death.

He is one of the lucky ones who made it out and is now living in relative safety in Thailand.

His story is not a unique one; a spokesperson for Reporters Without Borders tells us Myanmar has the second most imprisoned journalists in Asia, with 60 estimated to currently be behind bars.

The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners estimates over 28,000 people have been arrested since the coup, and that 6,203 have died as of January 23.

It is a story not often heard in the western world, where other conflicts overshadow the long fight between Myanmar’s military dictatorship and a plethora of rebel forces.

We hear James’ story at the main office of the now exiled Mizzima just outside Chiang Mai in Northern Thailand. The afternoon light is pouring in from the windows of the boardroom, where we sit opposite at a large conference table.

All the stuff was taken home to avoid capture.

It’s a long way from the prisons he endured, and it’s even further from where he grew up in southern Chin State, in the western part of Myanmar.

He made the long trip to the old capital Yangon in 2016, where he soon became involved with Mizzima.

“I came from the ethnic city, and even in the Burmese language, it was really difficult to read the news,” he says.

“I arrived in Yangon and was very interested in [how they] create this kind of news… curious about that. At the time, Mizzima announced job offers, and that’s why [I] joined Mizzima.”

He originally worked as a project coordinator, before working in the administration team, where he was in charge of organising training programs and training camps. It is something he still does today, as he is in charge of Mizzima’s Media Training Institute, running secretly inside of Myanmar.

There were no issues for a few years, until February in 2021, when everything changed.

The democratic government headed by Aung Sang Suu Kyi was overthrown by the military, and in an instant Myanmar went back in time.

Independent media was targeted overnight, and it wasn’t long before the Mizzima offices were in the firing line. James remembers the frantic first few days after the coup where they scrambled to protect themselves.

“[We] stayed [and] claimed all of the gear from the office and prepared for the raid of the junta. We prepare for four-five days since the 5th February. All the stuff was taken home to avoid capture,” he says.

“All of the gear, including computers, cameras, hard drives, all of them we have to keep safe.”

Then they started beating me.

Some Mizzima journalists and staff fled, but James stayed behind until he was arrested at the bank alongside the driver who accompanied him in a company car.

The pair were then taken to Yay Kyi Aing; its name in Burmese means ‘pure water pools’, but don’t let the idyllic name fool you. It is one of the most notorious prison camps in Myanmar.

He would spend 13 days there, and the interrogation started soon after he arrived.

“I was blindfolded when I arrived there at camp,” he says. “They asked, ‘what did you do with this money? Who would you support with this money? Where did you get it?’

“Then they started beating me.”

James says they were concerned with what the money was to be used for and where it came from and told us the interrogation and the beatings happened in his first two days at Yay Kyi Aing.

“They ask about the money, and I answered whatever I knew,” he says. “They asked a lot of questions — most of them I didn’t know the answer to — and whenever I answered ‘I don’t know’, they would beat me, punch me.

“There are two men asking me [questions] and two men on both sides of me, and whenever I answer, ‘no, I don’t know’, they punch me and beat me.

“Later I had to kneel down, but my heel and my bum could not touch. [I was in] a stress position, there was no relaxing. Whenever I answered ‘yeah [or] no or I don’t know’ they would beat me.”

He says they mostly hit him on his back and on his legs, but also remembers being punched in the face on multiple occasions.

James was subject to two days of interrogation at Yay Kyi I.

The freelance driver who was arrested alongside him was also subject to the same treatment after complaining to a soldier.

The beatings stopped after the second day, and he spent the remainder of his time in the camp in a small cell with another inmate. They were forced to share a very small bed and were not given a mosquito net, which meant they had to deal with mosquitos as well as the April sun.

“It was very hot, because in April in Myanmar [it’s] the hottest time, it’s really hot with the mosquito the whole night,” James remembers.

The ordeal was not just physical, as his captors also pushed his mental capacity to the limit.

“For the whole 13 days, every night they came and threatened again, ‘I can shoot you now with the guns!’” James says.

“[I was] just waiting [to] die.”

He would not die, and instead would be sent to another prison; a fellow inmate from the National Democracy League (NLD) gave James words of encouragement as he left the camp: ‘[They said] ‘now you will be sent to the prison, at least you… are safe, you won’t get killed.’ I feel relieved on that day.”

James was not the only member of Mizzima in the camp at the time: Amnesty International reported Mizzima co-founder Thin Thin Aung and another employee were arrested and tortured for two weeks before being transferred to Insein Prison.

He would join them there.

Whilst he says the prison was better than the camp, it was still a brutal place to be. Originally built in 1887 during British rule, it held political prisoners during the original military rule that came to an end in 2011, and for those arrested after the coup of 2021.

The cell James was kept in was described as a long hallway, approximately 60ft long and 20ft wide — not disimilar to the boardroom we are in now. He says there were 80 inmates per cell.

There were no beds to sleep on, so all the inmates had to crowd around on the floor. He remembers having little privacy and nowhere to wash his hands or dishes.

James also remembers insects being a constant presence for the first part of his stay, making the conditions even more uncomfortable.

An aerial shot of Insein Prison in Yangon. (Source: Google Maps)

He was later moved to a second section where the cell was bigger and there were less people. He remembers now having a basin for washing, and also having enough room to sleep on the floor at night — there were still no beds.

James was interned at Insein until October, when he was visited by a ministry agent.

“A ministry agent came to the prison and met me,” he says. “[They said] ‘you will be released tomorrow, but please don’t tell anyone else. Keep [it] secret.

“And then next day, they announced who will be released, and my name was first, number one.”

James was unsure of why he was given amnesty; we are told wide-scale release of prisoners is normally reserved for January 1 — Myanmar’s Independence Day – and on April 17, which is the New Year in the Burmese calendar.

“I think the reason why they call amnesty is because there is almost eight months or 10 months of the coup, and they arrest many of the people, and they want to show ‘we give them amnesty’ for… political statement,” James says, theorising it was a show of compromise from the junta.

The prison authorities even offered to take James home, but he rejected the offer, still believing it and his release to be a ruse.

“I didn’t believe when the military agent met me, because the first amnesty happened on June, and I didn’t get it at that time. And then the second one I stayed not believing I would be released,” he says.

James returned home and tried to move on, but it was never going to be easy after an almost seven month ordeal of torture and imprisonment.

“I couldn’t sleep well. [I was scared] I might get arrested again, and whenever I move or go out, I didn’t feel safe,” he says.

“[I] feel like someone is following me.”

He remembers being warned by the military agent who visited him in prison not to become involved with independent media or to report in the state, being told explicitly: ‘If you want to stay in the media don’t go against the state or the government.’

I am trying to forget… Of course it has a lot of impacts, I am trying to forget about that, trying not to think about that.

James got in contact with Mizzima’s founder Soe Myint, who offered to help him get out of Myanmar.

He made it to Chiang Mai via Karen State and Mizzima’s training centre, arriving in Thailand in January 2022.

He has since continued his work with Mizzima, primarily organising the camps that continue to find and train journalists to do incredibly brave reporting work within Myanmar, despite being under heavy threat of military and police punishment if caught.

After everything James went through purely for his association with Mizzima, it would be easy for him to want to walk away, or to regret becoming involved in independent media in the first place.

That couldn’t be further from the truth.

“There is no regret working in Mizzima,” he says.

“Of course I experienced those very bad [things]. [But] I am really proud working with Mizzima, because Mizzima is presenting, making news on what is really happening on ground.”

“I’m very proud of that, no regret!”

It is fairly remarkable to hear James speak so candidly about the physical and mental torture he went through in his imprisonment. He is not only brave for going through such an experience, but also to share it to total strangers and to a wide audience.

There are still signs the trauma remains, though.

“I am trying to forget,” he says.

“Of course it has a lot of impacts, I am trying to forget about that, trying not to think about that.”

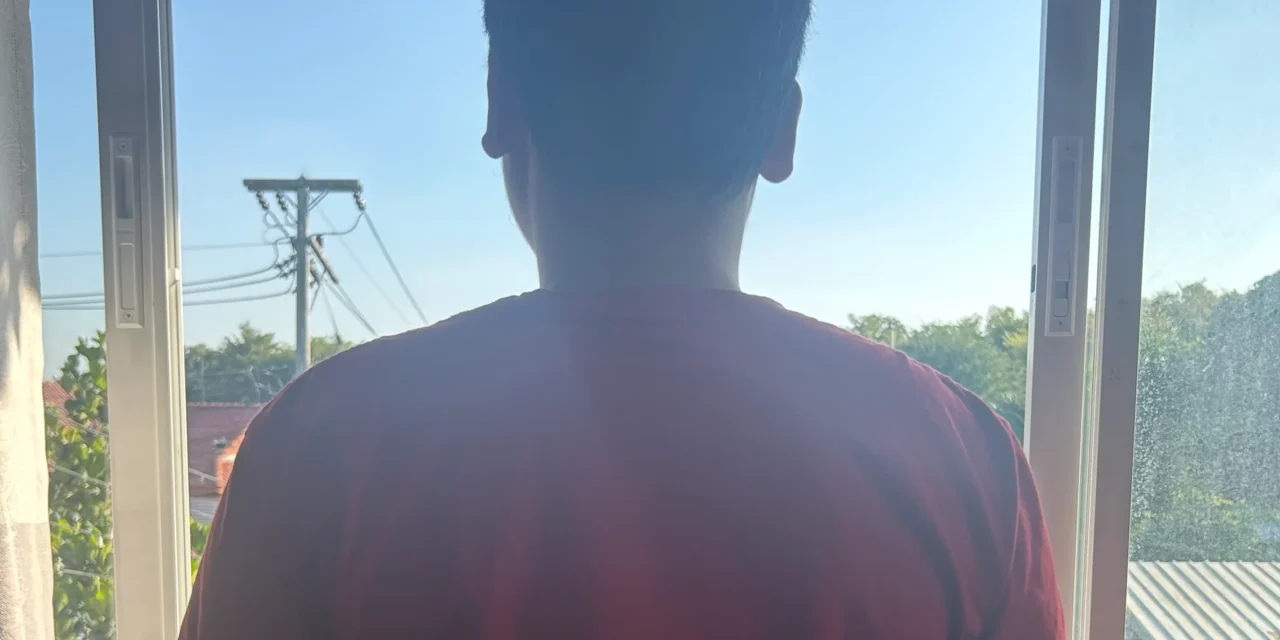

*This is not his real name. We are using a pseudonym to protect his identity.

Main image by Patrick Brischetto

UTS journalism students travelled to Thailand as part of The Foreign Correspondent Study Tour, a University of Technology Sydney programme supported by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s New Colombo Plan, and working with Chiang Mai University strategic communications students in association with Chiang Mai University.

@PatBrischetto