The Haunting of Woodford Academy

Every town has its folklores. This one has ghosts.

by Emily Kowal

Nestled within the Blue Mountains is a town with a secret.

Small, quaint and all-but hidden by a shroud of heavy eucalyptus trees, Woodford could easily go unnoticed…

… if it weren’t for its ghosts.

Like the roaring Great Western Highway that cuts through Woodford’s centre, ghost stories divide this town.

Bill Evans is at the perimeter of the Woodford Academy. He stands with his wife, staring up at the old building.

Over the screaming cicadas, we introduce each other with raised voices. “We wouldn’t go any further until you got here,” he says.

That’s partly because he wanted to make sure we were allowed to be here. After all, the Academy is private property, with access only granted by the Blue Mountains Trust.

He seems uneasy as he slides the wooden gate open. A blue tongue lizard scuttles under the lavender bushes next to us and we all jump.

“I know what goes on here. This place is odd. Things happen. And they happen completely out of the blue. You could be doing something normal like demolishing a toilet when all of a sudden an old lady is standing there, watching you through a window.

“I would never ever spend a night here on my own. And I don’t think many people in the district would either.”

Built nearly 200 years ago, Woodford Academy has a rich and tragic history.

Its sandstone blocks are infused with a myriad of ghost stories.

Tales of troubled souls tapping against a window and looking onto the highway have become town folklore.

In the light of day it is easy to think of these as simply stories told over a campfire.

But the unease in Bill’s voice shows he begs to differ.

A surveyor with an engineering background, Bill Evans has lived his life guided by numbers and evidence.

He’s lived in Woodford for over 70 years and for most of that time the Academy and its stories were no more than childish fodder – nothing to believe in.

This changed when he took on the role of Vice-President of the Blue Mountains branch of the National Trust, a role which saw him work closely with the Academy, and visiting the building regularly.

For Kate O’Neil, the Woodford Academy is an old friend. As chair of the Woodford Management Committee and the Academy’s collections manager, she has become well acquainted with the nearly 200-year-old building.

She walks around, slipping skeleton keys into antiquated locks – the building’s history pouring out of her with ease.

Originally constructed in 1830, the building is the oldest surviving complex colonial structure in the Blue Mountains. It has been used as a guest house, a gentleman’s residence, a boarding house and most famously, the exclusive school called the Woodford Academy.

Listening to Kate talk, it is easy to forget that the building has been touted “Australia’s most haunted”. She gestures to the myriad of portraits dotting the walls, faded reflections of the past, and introduces me to the characters that once roamed the floors of the building.

Kate’s love of the Academy is clear – she appears to take personal offence at the suggestion that her beloved figures could still linger in the halls, terrorising guests. “It’s great. It’s a place that is 190-years-old, so of course it is going to have a lot of natural energies [and] life stories, and I am all for that.”

When I ask Kate about the ghost stories that linger, she is matter-of-fact: “Because of its age and long association with different types of people, it does have a few supernatural stories. Some of those are recent, and some go back to the 1800’s. Of course, they are only made worse by sensationalism.”

Like many old buildings, the Academy has a colourful history; punctuated by moments of death and disease set against a backdrop of European colonialism and Indigenous dispossession.

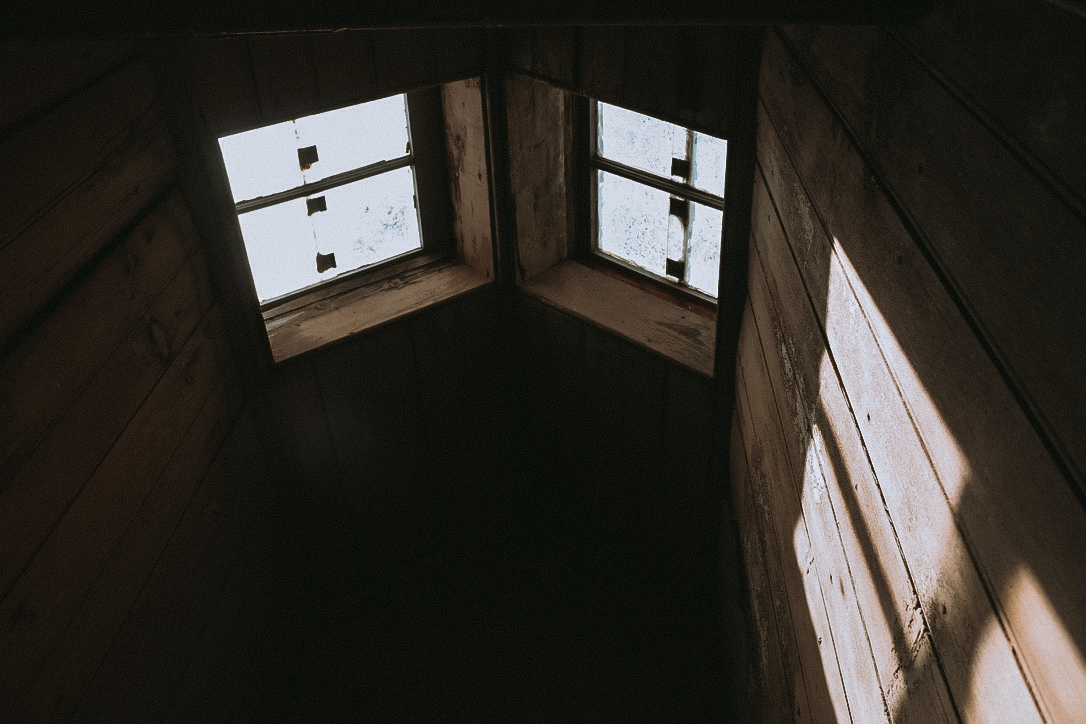

I follow Kate up a flight of stairs so steep they are almost vertical. She leads me to the room of the Academy’s most notorious haunting,

“The Lady In White”.

Ducking under the low ceilings, Kate travels back to 1835. She tells the story of Mary James. It’s a tale that’s horrific because it is true. A mother of six, Mary struggled with mental illness and domestic violence – factors which led to her eventual suicide.

Kate shows me a clipping from The Sydney Gazette and NSW Advertiser dated Tuesday 16th August 1836. It reads: “The husband who was then present (at Mary James’ suicide attempt), said she was ‘not game enough to do it’. She, upon being taunted, tied herself up again and kicked away the box.”

Mary James’ legacy has evolved into that of a troubled spirit who lurks the Academy’s halls, peering out windows and frightening visitors.

When asked if she believes in ghosts, Kate laughs. “The only ghosts in Woodford Academy are the ones that people bring with them. There has been death at the Academy, sure, but there has also been life. I don’t mind people coming and experiencing whatever they want to experience but just don’t distort the historical reality, and if you do say there are ghosts, they might be your own.”

“The only ghosts at the Academy are the ones people bring with them.”

According to Australian-Indonesian journalist and researcher of urban legends Tito Ambyo, there’s a certain truth to Kate’s belief that humans bring their own ghosts with them.

He explains that our ongoing fascination, despite this age of scientific realism, can be attributed to one thing: “Ghost stories have become a way for us to see what we find fearful.”

“Every time we tell a ghost story, it is a new story. What we find fearful at the time will become a part of the ingredients of the storytelling.

For instance the Lady in White. You see a version in India, you see a version in Indonesia, you see a version in Australia – it’s all throughout the world. It might be an old story, but every time that story is told, it has new ingredients. Maybe at one point, the lady in white was a girl who was killed because she was thought to be a witch. But today, the lady could be seen as someone who died from domestic violence.”

Ghost stories have become a way for us to talk about the fears that linger beneath the surface. “Let’s take for example stories which involve domestic violence,” he adds. “Sometimes it can be too hard to talk about but, using ghosts, we can talk about a very important issue while also engaging the other emotion we have surrounding this topic, which is fear.

“A lot of the best lingering ghost stories go deep into the challenges that we are facing as a society… they help us understand and empathise with people who may have been victimised.”

When asked if he personally believes in ghosts, Tito smiles widely. “There are people who already believe in ghosts and will share the stories because they believe ghosts exist and are affecting the way we live. On the other hand, there’s another group of people who are probably a little bit like me; we want to be convinced, we want to find the evidence because we love the stories.”

Even the biggest sceptics, Tito explains, will have their moments of doubt.

“Humans are complex. We aren’t black and white; we can’t just have a blanket statement that ‘I don’t believe in ghosts’. Because I know for me there have been moments in my life where it was like ‘oh hold on… what is this weird thing that I am feeling?’ Even though my brain is saying it is impossible, I have to acknowledge that there’s something there”.

For Pete Clifford, society’s ongoing fascination with ghost stories such as those that trail the Academy, has become a way of making a living. For the past 20 years he has worked as a professional ghostbuster, making a business out of exploring ghost stories and appealing to our often morbid curiosity.

When we meet at Katoomba, the sun is setting and a thick mist is settling over the mountain top. Working at a limited capacity, his ghost tour bus is intimate, just six of us huddled together. Excitement and the occasional monotone sound of ghost-hunting equipment crackles in the air.

Over the course of five hours he takes us through the Blue Mountains – deep into the forest and into hidden cemeteries. Like many of the stories at the Academy, the origins of Pete’s fables are riddled with traces of domestic violence, dispossession, mental illness and abuse.

He views ghost stories through a pragmatic lense. Rather than sensationalise them, he sees himself as a fact-checker, valuing authentic, evidence-based stories over all else.

“Normally I will know the story from the local area, but before I take people on a tour, I will go back and search through newspaper articles [and] Trove, [and] I will talk to historians.”

Throughout the night, Pete relays his own paranormal experiences, many of which happened at The Academy.

“I have seen people being scratched there. We have had an aport when something goes from one room to another. Probably one of the scariest things was when I saw Mary James, The Lady in White, in the mirror. It actually felt like she tried to grab me. We have smelt cigarettes there, we have smelt alcohol. Disembodied voices at times. Often when we go there, people will feel overcome with a feeling of dread.”

While Pete certainly believes in ghosts, he does not try and convince others along the way. As he explains, he simply lets them see what they see.

“We get a lot of people who come who didn’t really believe, they just came along for the history side of it. A lot of people go away and they aren’t, you know, converted – but they have opened up their minds a lot more.”

By the end of the night we have not seen any ghosts, but we leave haunted by their possibility.

— Story, photos and video, Emily Kowal